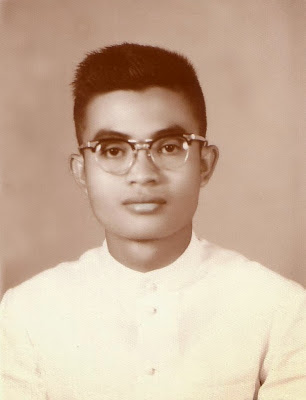

Bro. Isagani Valle was born on December 28, 1959 in Mahayang, Zamboanga. Originally, his parents were from Ormoc City but the search for greener pastures led his parents to leave their beloved city. New opportunities led the family to move again to San Francisco, Agusan del Sur where the siblings of the family continued their education.

He took his High School education from Father Urios, High School of San Francisco, Agusan del Sur which was administered by the Carmelite Fathers and Brothers. Gani showed exceptional intelligence and friendly character to his classmates. They would describe him a very patient person, smiling and always ready to help those in need, especially his poor classmates. Inspired by the priests, his vocation to become a priest grew in Isagani. At one time, when the family returned to Ormoc City, Brother Gani decided to take the examination of priesthood in Palo Diocese which he easily passed.

the year 1972, he was a seminarian in the seminary in Palo. His classmates (Monsignor Bernardo Pantin and Fr. Manuel Ocaña) testified that he always topped their exams when they were seminarians in Palo. When his family moved back to Agusan, he left the Diocesan Seminary to join them. He became active in the Parish of the Sacred Heart administered by the Carmelites in San Francisco, Agusan del Sur. This service in the parish, ignited in him once again, the passion to become a religious.

Inspired by the service the Carmelites rendered to the community of Agusan, Isagani decided to join the Carmelite Order despite of the fact that he passed other scholarships for College studies. From the period of 1977 until 1981, he studied as a Carmelite seminarian in the Our Lady of Angels Seminary (OLAS) and St. Joseph’s College in Quezon City.

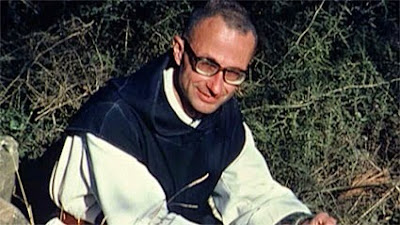

During his novitiate formation, he got involved in different student organizations which demanded change in the unjust structures of the Philippine government. He received his temporary profession to the Order in the year 1982. Gani is remembered by us through his advocacy with the poor and the marginalized. His words of passion for people so reflected in the following excerpts from one of his study-group reflections expressed his unwavering stance for justice:

“We still have to see a theology that proceeds from the people and goes back to the people; a theology which contains the lives and experiences of the masses; a theology that is dialogical. This needs real immersion in the lives, sufferings and struggles of the people. It is being written in the midst of the slums, in dialogue with the poor and their life-situation: It is that place where we, seminarians, have to listen and learn. It will, for sure, be different from a theology written in airconditioned rooms. We must work and struggle for this theology – liberative and developmental of the people, and transformative fo reality.”

He lived out these words. The Carmelites let their seminarians experience the poorest of the poor during their exposures that they may live out like Jesus Christ who once preached, "foxes have holes, birds have nests but the son of man has nowhere to lay his head." During one such exposure in Mindanao specifically on May 14, 1983, he was killed by the police while having his exposure/immersion in Buenavista, Agusan del Norte. He wanted to get a first-hand experience of what life was like for poor people living on the edge between military violence and liberation.

While attending a fiesta in Buenavista, he was seen strolling around with two companions farmers who were suspected to be members of the New People’s Army. Following a tip of an informer, the police force of Buenavista suddenly swooped upon them and mowed them down under a rain of bullets.

Their bullet-ridden bodies were displayed in front of the Municipal Hall of Buenavista and buried afterwards without a coffin in a common grave at a cemetery. His life inspired his religious friends. Sr. Asuncion Martinez, ICM to write a tribute for him:

Brother Gani!

With pride and deep reverence

We salute you,

Our youthful hero and martyr.

With longing you had desired to be a PRIEST.

A priest of God, with a heart of flesh –

To love, to serve, to pray, to sacrifice for our oppressed,

and exploited dehumanized BROTHERS.

Brother Gani,

In this crucial time of our people’s history,

You wanted to plunge yourself

into the stream of our struggle

to be ALL things to all.

Perhaps, you wanted to be the priest of the slums,

Among the homeless and jobless;

To be the labor-priest

standing by the striking workers,

Or the priest crawling and groping

In the black tunnels of collapsing mines.

You wanted to be a priest among

Our uprooted peasants, dumped and herded

Inside company plantations; harassed and

driven away from their smoking villages.

Or a priest

ministering to the Tingguians and Kalingas

at the foot of the Cordillera mountains.

Or somebody among the Manobos and T’bolis

of Mindanao, withering and starving in

their dried cracked gaping fields,

having nothing to harvest, nothing to eat

nothing to plant.

Surely Gani,

Your supreme desire

was to be a priest

among our brother revolutionaries,

stationed in the jungles and mountain passes,

fighting for JUSTICE-FREEDOM

for our COUNTRY and our PEOPLE.

Brother Gani,

As you saw the vastness and urgency of your mission,

You could no longer wait for your ordination day!

You boldly ventured into treacherous paths

and forbidden grounds to bind

the wounds of those who had fallen

by the wayside, to defend the scattered sheep

against the hungry wolves.

But above all you craved and hungered

for the glorious embrace

of your brothers in the struggle.

Brother Gani, this was your last and deepest dream.

Yet a dream that was suddenly blasted by the gun,

and by a traitor’s bullet

snatching you away from us and our people.

Brother, that day became your solemn ordination day.

You then became truly a priest,

Our prophet, our martyr –

Anointed with your own blood,

vested in priestly robes of bleeding scarlet.

As your temple, you had only the open skies

and as your altar the very soil

moistened by your blood.

No bishop to consecrate you

but only the loyal and daring poor

who tenderly and reverently lifted

your broken body

for the salvation and liberation of our people.

Brother Gani,

people thought you were alone

for your solemn mass –

no, you were not alone.

You passionately carried in your heart

Your downtrodden brothers

and all your faltering fellow religious

and church workers,

to celebrate with you,

in your first and last Mass,

your Mass of Resurrection.

Gani,

infuse into the very depths of our being

your indomitable courage!

Courage to dare to speak out the truth,

Courage to fight for justice

Courage to work relentlessly

for Freedom of our country!

Gani, they have killed you

but they can never silence you.

Your prophetic voice resounds

in every church, school and seminary

Oh! May it never stop!

Until the last priest and nun, brother,

pastor, deacon, seminarian, pastoral worker

has valiantly joined the struggle,

the march to freedom,

towards our final Resurrection

as a fully liberated people in a land

where there are no more tyrants

no more slaves,

“where there will be no more death,

no mourning nor crying no pain.” (Rev. 21:4)

Father Isagani,

we proudly salute you

our PRIEST, our PROPHET,

our HERO and MARTYR,

our very own BROTHER!

Brother Isagani's body has been transferred from San Francisco, Agusan del Sur to the Catholic cemetery of Ormoc, Leyte. He is buried beside his father and other relatives. On his tombstone is written the words, "IN OBSEQUIO IESU CHRISTI" for indeed he died IN ALLEGIANCE TO JESUS CHRIST whom he followed even unto his death.