May 21, 2015

A Short Way of the Cross

This shorter way of the cross

is used by Franciscan Missionaries in mission

who do not have ample time

to use the usual form.

O Jesus! so meek and uncomplaining, teach me resignation in trials.

Second Station Jesus Carries His Cross

My Jesus, this Cross should be mine, not Thine; my sins crucified Thee.

Third Station Our Lord Falls the First Time

O Jesus! by this first fall, never let me fall into mortal sin.

Fourth Station Jesus Meets His Mother

O Jesus! may no human tie, however dear, keep me from following the road of the Cross.

Fifth Station Simon the Cyrenean Helps Jesus Carry His Cross

Simon unwillingly assisted Thee; may I with patience suffer all for Thee.

Sixth Station Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus

O Jesus! Thou didst imprint Thy sacred features upon Veronica's veil; stamp them also indelibly upon my heart.

Seventh Station The Second Fall of Jesus

By Thy second fall, preserve me, dear Lord, from relapse into sin.

Eighth Station Jesus Consoles the Women of Jerusalem

My greatest consolation would be to hear Thee say: "Many sins are forgiven thee, because thou hast loved much."

Ninth Station Third Fall of Jesus

O Jesus! when weary upon life's long journey, be Thou my strength and my perseverance.

Tenth Station Jesus Stripped of His Garments

My soul has been robbed of its robe of innocence; clothe me, dear Jesus, with the garb of penance and contrition.

Eleventh Station Jesus Nailed to the Cross

Thou didst forgive Thy enemies; my God, teach me to forgive injuries and FORGET them.

Twelfth Station Jesus Dies on the Cross

Thou art dying, my Jesus, but Thy Sacred Heart still throbs with love for Thy sinful children.

Thirteenth Station Jesus Taken Down from the Cross

Receive me into thy arms, O Sorrowful Mother; and obtain for me perfect contrition for my sins.

Fourteenth Station Jesus Laid in the Sepulchre

When I receive Thee into my heart in Holy Communion, O Jesus, make it a fit abiding place for Thy adorable Body. Amen.

Father Rufus Halley

|

| Father Rufus Halley |

I first met Father Rufus Halley in the mid-1970s when I was appointed auxiliary bishop in Manila with responsibility for Rizal Province, the area that became the Diocese of Antipolo in 1983. The Columbans had been working in parishes there since before the War. Father Rufus was in Jalajala at the time. Father Feliciano Manalili, a diocesan priest, introduced me to him. Father Manalili is now a Trappist monk in Mepkin Abbey, South Carolina, USA, where he is prior.

New friend

At first I knew Father Rufus in a formal way, as one of the parish priests under my jurisdiction. But I gradually began to know this man with an open personality and a wonderful sense of humor as a person. On one occasion he invited me to a barrio in his parish that was 45 minutes by boat from the centro. He had forewarned me that this would be a different kind of pastoral visit. We set off in the afternoon. The house where we stayed was on a duck farm and some of the birds were waddling around the house. There was no electricity. After dinner we walked around the village. I saw the people at their usual occupations that included drinking and gambling games such as bingo. Father Rufus introduced me as ‘my friend from Manila,’ which wasn’t untrue, as we were in the Archdiocese of Manila.

Back at the house we chatted for a long time and prayed together. We decided we’d celebrate Mass the next day back at the centro. We slept on the floor. As we were leaving next morning people came to see us off and it was only then that their parish priest told them that I was the area bishop. Though there was some embarrassment, especially among those who were members of Church organizations, there was a lot of laughter at the realization that the bishop had met them as they really were.

Tagalog speaking Irishman.

By this time Father Rufus and I were close friends and I called him ‘Pareng Rufus’ and he called me ‘Pareng Dency.’ I felt free to drop in on him any time and to go through the back door of his convento. Sometimes I wouldn’t find him in the office or upstairs and would then realize that, despite his red hair and blue eyes, I had passed him in the kitchen, where he was chatting with the staff. (His baptismal name was Michael but his parents always called him ‘Rufus’ because of his red hair). What threw me was that I’d hear only pure Tagalog while walking through the kitchen. My Irish friend spoke the language perfectly.

|

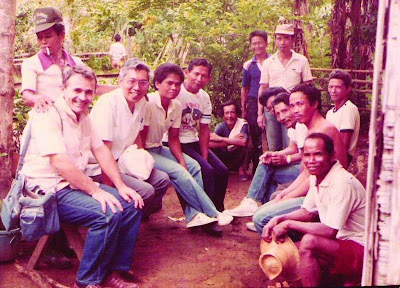

| Father Rufus Halley with the author, Gaudencio B. Cardinal Rosales |

Another trademark of Father Rufus was his bakya. I learned from the late Father Patrick Ronan, then parish priest in Morong, that Father Rufus came from a privileged background. That was a revelation to me, as I had always been struck by the simplicity I saw in his life. Father Ronan, another Irish missionary with a great sense of humor and known to his fellow Columbans as ‘Pops’, had spent time in jail in China after the Communist takeover in 1949.

Around 1980 Father Rufus felt called by God to leave the security of living in an overwhelmingly Catholic community to work in the new Prelature of Marawi, which includes all of Lanao del Sur and part of Lanao del Norte, where 95 percent of the people are Muslims. He was very aware of the long history of tension and occasional outright conflict between Christians and Muslims. He also became fluent in two other languages, Maranao, spoken by the Muslims in the area, and Cebuano, spoken by the Christians.

His kind of dialogueo

I too moved to Mindanao, becoming Coadjutor Bishop of Malaybalay in 1982 and succeeding Bishop Francisco Claver SJ in 1984. On one occasion, after spending about a week on retreat in the Benedictine Monastery of the Transfiguration in Malaybalay, Pareng Rufus came to spend a night at my place. He spoke of a ‘brother Muslim’ whom he loved very much and told me that he had been hired to work in a store in the market in Malabang, Lanao del Sur. ‘Why?’ I asked him. ‘This is my kind of dialogue,’ he told me. He was pushing Christian-Muslim dialogue to the limit. When the late Bishop Bienvenido Tudtud, first bishop of the then Prelature of Iligan, which covered the two Lanao provinces, told Pope Paul VI of the conflict there and of his vision of a ‘dialogue of life’ between the two communities, the Pope encouraged him to the extent of dividing the prelature and transferring him to Marawi. Bishop Tudtud died tragically in a plane crash in 1987.

|

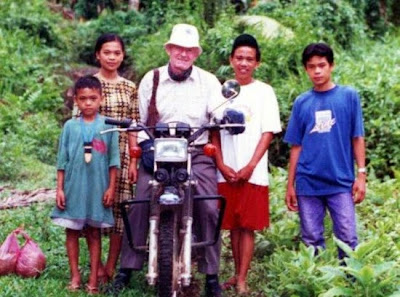

| Father Rufus Halley with Maranao-Muslim friends |

Male dominated Maranaos

My friend Rufus wanted not only to know the faith and culture of Muslims but to ‘befriend the culture of our brother Muslims.’ More than that, he wanted to understand the culture of the Maranaos. This involved trying to understand aspects of that culture that went against his own warm nature and that didn’t seem to be in harmony with the Gospel. For example, he noticed that among Maranao men it wasn’t seen as proper to show any public signs of softness, even if a child of theirs was hurt. He noticed how stiff Maranao men are in their dances which many Filipinos are familiar with. Men sometimes carry a kris as a sign of power. He was well aware that many men, Christian and Muslim, carry a gun for the same reason, and not only in Lanao. He asked himself if there were any areas of tenderness in the macho culture of the Maranaos and stressed the importance of trying to find ways in which the Gospel could enter into dialogue with that culture.

Pareng Rufus was really educating me that night.

Who inspired himo

I knew of the intensity with which Father Rufus lived his own Christian faith, how he began each day with an hour of adoration before the Blessed Sacrament, the centrality of the Mass in his life. A big influence on him was the life of Charles de Foucauld, 1858-1916, beatified last November. This Frenchman was also from a privileged background. Unlike Pareng Rufus, he lost his Catholic faith and became a notorious playboy before re-discovering it, partly through the example of Muslims living in North Africa. He spent many years as a priest living among the poorest Muslims in a remote corner of the Sahara, pioneering Christian-Muslim dialogue by discovering himself as the Little Brother of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament and as the Little Brother of the Muslims who came knocking at his hermitage door.

Death of a peacemaker

On 1 December 1916 Charles de Foucauld died at the hands of a young gunman outside his hermitage and on 28 September 2001 Pareng Rufus died at the hands of gunmen who ambushed him as he was riding on his motorcycle from a meeting of Muslim and Christian leaders in Balabagan to his parish in Malabang. The local people, both Christian and Muslim, mourned for him deeply. The grief of the Muslims was all the greater because the men who murdered my Pareng Rufus happened to be Muslims. This great missionary priest brought both communities together in their shared grief for a man of God, a true follower of Jesus Christ.

Fr. Godofredo Alingal, S.J.

|

| Fr. Godofredo Alingal, S.J. |

Fr. Ling’s first assignments were in the province of Bukidnon, moving to Ateneo de Naga, Cagayan de Oro City, and in 1968, back to Bukidnon.

At that time, the Catholic Church was seeing dramatic changes as an aftermath of the Second Vatican Council. The Gospel was henceforth to be preached beyond the walls of the church, and in the fields, market places, the hills, and lived as a witness to give people back their dignity and their rights.

Fr. Ling embraced these new church teachings, preaching as well as practicing them with his flock. He found Bukidnon a land of great social conflicts. Politics was rough, and bullets counted more than ballots. Peasants were oppressed by landlords, usurers and middlemen, and power was in the hands of a small few.

Fr. Ling’s involvement with farmers began by helping them start a credit union and a grains marketing cooperative. He helped organize the Kibawe chapter of the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF).

|

| Fr. Godofredo Alingal, S.J. |

Gentle and soft-spoken, Fr. Ling nevertheless spoke out against electoral fraud, threats and harassments by the military, denouncing these from the pulpit and through the prelature newsletter Bandilyo. In 1977, the martial law government closed down the prelature radio station DXBB, and Fr. Ling, refusing to be cowed, started the Blackboard News Service, a giant blackboard in front of the church, broadcasting news otherwise being suppressed, and as always, denouncing official abuses. The blackboard was vandalized repeatedly, but Fr. Ling, exhibiting both patience and determination, simply put up a new blackboard to replace it.

Fr. Ling’s advocacy for clean elections in 1980 earned him a written death threat: “Stop using the pulpit for politics … your days are numbered.” He received another death threat months later. But he told himself, “What else is there to do -- the priesthood is not a safe vocation.”

He had just gotten orders for reassignment to another parish in April 1981, when assassins swooped down on his parish and killed him on the evening of the 13th of April. Two parish houseboys having gone out to lock up the church for the night were suddenly crying for help. The priest, wanting to know what was happening, opened his door to five men, armed and wearing masks. A .45 caliber automatic was aimed at him, one bullet going straight through his heart. Two men then ran up to cut off the church’s electric connection. Then they all fled on motorbikes. A physician living nearby rushed to the church when he heard the shot. Fr. Ling died in his arms.

He was 59.

Two bishops and about 70 priests, including then Jesuit Father Provincial Joaquin Bernas, concelebrated the funeral mass for Fr. Ling. Thousands coming from the town proper and the surrounding barrios and towns joined the funeral march, bringing with them placards, painted with the angry query: "Hain ang justicia? (Where is justice?)” People across Bukidnon expressed their outrage over the priest’s killing.

Can the poor receive communion?

|

| Fr. Fausto 'Pops' Tentorio |

October 8, 2014

This question is hard. I know. Hard on the poor. It might be hurtful to them. But this question is not against them. They know that.

In my country, Chile, it's normal for the poor to form their families little by little. When life smiles on them, they come to have their own house and, if they're Catholics, they get married in the Church. There is nothing more wonderful than a religious marriage celebrated after making a long journey of great effort, with all the winds against you. The best of all worlds is having reached this point, having brought up your children and still having the strength to take on the grandchildren.

The working class family is a miracle. It consists of people who tend to come from very precarious human situations, have gotten ahead by overcoming great adversity and, if that weren't enough, bear the scorn for being poor. Society looks askance at them and blames them for their destitution! They do not live as they should.

She already had a child. She got pregnant at fifteen. He also had a child elsewhere. They fell in love and went off to live together in a room they could rent. But in a few months, life there became impossible for them. The child cried. The bathroom wasn't enough for everyone. In the refrigerator, they had a minimal space reserved for the baby bottle and nothing more. There were rumors of a land takeover. A political party offered them a share. They decided to run the risk because it was dangerous to try it. In the camp, a third child was born...of both of them. Together the four withstood the lack of water, the filth, the trips to the hospital, the bad environment...Thanks to the leaders and the assemblies, they fought for a house and got it. Getting married in the Church never crossed their minds. Civilly, yes. But they didn't want to do it until they could offer a fiesta in the place they would live forever. In the meantime, she arranged to leave the children with a neighbor and thus be able to be employed in a private home. He, a construction worker, was a real go-getter. He rarely lacked work. But to get to the job, he often had to take two buses, a trip that took him an hour and a half or two hours in all.

What piety is possible under these living conditions? A very deep one. I know. It's not a matter of talking about it. I would have to extend my remarks. I just want to make it known that the working class Christian communities are composed of people like these. They themselves are the ones who got land for the chapel, built it, and water the garden. These same people are responsible for the catechesis of their children. In these communities, at Sunday Mass, at the moment of Communion, no one is denied anything.

If the poor couldn't receive communion, the Church wouldn't be the Church.

Sr. Dorothy Stang: Living in Extreme Poverty with the Poorest of the Poor

|

| Sr. Dorothy Stang |

On a rain-soaked Saturday in February 2005, she carried that Bible while making her way along a muddy Amazon jungle road. She was headed to Boa Esperança, a village near Anapu, where she lived in the northern Brazil state of Para. The area lies on the eastern edge of the Amazon, a region known for its wealth of natural resources and the violence that boils over from land disputes.

Waiting for Sr. Dorothy that morning was a group of peasant farmers whose homes had been burned down to the ground on the land which the federal government had granted to these farmers. In the entire state of Para and in a place like Boa Esperança, legal title to land does not always end disputes. In Para, logging firms and wealthy ranchers find assistance from local politicians and police in procuring and commandeering property from indigenous peoples and small farmers. While Sr. Dorothy walked on toward Boa Esperança, she heard taunts from men who had stopped alongside her. The rain poured as she stopped and opened her Bible. She read to the men. They listened to two verses, stepped back and aimed their guns. Sr. Dorothy raised her Bible toward them and six shots were fired at point blank range. She fell to the ground, martyred.

In the days preceding her murder on February 12, 2005, Sr. Dorothy was attempting to halt illegal logging where land sharks had interests but no legal rights. Authorities believe the murder was arranged by a local rancher for $19,300 (U.S.). Many believe that a consortium of loggers and ranchers had contributed to the bounty on Sr. Dorothy’s head in an effort to silence her. Ironically, their attempt at silence resulted in an opposite effect: an outraged world, well informed about the murder through persistent global media reports, sent Sr. Dorothy’s voice soaring to new heights. And a proclamation came quickly from Brazil’s President Luis Inacio “Lula” da Silva, that the land in question, over 22,000 acres, would be reserved for sustainable development by the poor farmers whose cause Sr. Dorothy had championed.

Following her death, Brazil’s Human Rights Minister, Nilmario Miranda, described her as “a legend, a person considered a symbol of the fight for human rights in Para.” While this accolade has become global consensus, Sisters who knew the down-to-earth Sr. Dorothy state that she would have cringed at being called a legend. Having spoken with Sr. Dorothy days before her death about threats against herself and others, Mr.Miranda says: “She always asked for protection for others, never for herself.”

Her Sisters, family, friends and colleagues gathering around tables, at prayer services and in classrooms around the world, try to understand the pattern of fact and circumstances that led to Sr. Dorothy’s death. Many are curious to know more about her ministry and what brought her to Brazil in the first place.

Like most Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, Dorothy Stang chose life in this Congregation which has a clear preference for work among those living in poverty. At age 18, she completed her application to join the Sisters and wrote boldly across the top of the form: “I would like to volunteer for the Chinese missions.” She never served in China, but her dream of missionary work was realized in Brazil.

Sr. Dorothy lived and worked in Brazil for nearly 40 years. She went there for the first time in 1966 with five other Sisters of Notre Dame. At that time, Sr. Dorothy and her Sisters spoke little or no Portuguese. So they began the ministry with language learning. Soon they established a new convent at Coroatá in the state of Maranhão, where they trained lay catechists and gave religious instruction to adults. Over time, the Sisters became more aware of the social problems troubling this region, particularly the oppression of farmers. The Sisters reacted by stressing basic tenets of human rights in their lessons and their work took on new proportions and expanded to new areas in Brazil.

Sr. Barbara English was among the group who traveled to Brazil with Sr. Dorothy. She remembers: “By 1968, all of us (SNDs) in Brazil were aware of the repression and violence promoted by the military dictatorship. People who worked for human rights and for the small farmers’ rights to the land were labeled subversive and the military dictatorship had them hunted down.”

In the early 1970s, Brazil’s government touted the benefits for impoverished people to move to the Transamazonian region. Landless people saw this as an opportunity to become farming homesteaders. Many moved to the state of Para to begin new lives for their families. This sparked in Sr. Dorothy something that would have attracted many Sisters of Notre Dame — the chance to help people create better lives for themselves. She packed up and joined the farmers on their journey to the new frontier but once there, they all realized that the poverty and insecurity they had left behind had been replaced by new problems: land sharks, intent on occupying the soil they had come to till, were taking over. Officials in Para offered no remedy since many police and politicians were well paid to scare off the homesteaders.

The farmers who had traveled to the region on the advice of the Brazilian government found their dreams of independence and security for their families not only elusive but dangerous. So they moved even deeper into the forest, and Sr. Dorothy moved with them. Still, the situation was the same after each migration and, according to Sr. Barbara, it became obvious by 1980 that the government had other plans for the region.

The Great Carajás Project designated 10.5 million acres in northern Brazil for development encompassing three states, including Para. Sr. Barbara recalls: “This sector of Brazil held every imaginable mineral deposit along with potential highways, railways and waterways for transportation, as well as potential dams for energy.” The plan was to open the land for mining, refining and agribusiness projects.

“They were David facing Goliath,” said Sr. Barbara, of Sr. Dorothy and the peasant farmers, “and Goliath came in the form of multinationals, big businesses, ranching and lumber companies ... They began to devour the Amazon forest.” (Environmentalists estimate that the Amazon loses 9,170 square miles of forest every year and that about 20% of its 1.6 million square miles has already been cut down to make cattle pasture or to log cedar, mahogany and other precious hardwoods.)

Sr. Dorothy and “her people” moved still further into the forest. Her dream of landless families safely engaged in sustainable development projects brought her ultimately to Anapu, Para in 1982. There, she worked to develop a new type of agrarian society that helped farm families from diverse cultures develop common bonds and learn how to use the soil to sustain themselves and the land. With Sr. Dorothy’s help, the communities in Anapu lived in solidarity and with respect for the environment. During these years, she worked with the Pastoral Land Commission, an agency of the Bishops’ Conference in Brazil. She also helped to foster small family business projects in the village, often creating, for the first time in many families, women breadwinners.

“She helped train agricultural technicians and worked hard to create a fruit factory,” said Betsy Flynn, SND, a Sister of Notre Dame whose ministry has also brought her to Brazil. Sr. Betsy remembers Sr. Dorothy as a person supporting the community she helped build through education and health care. “She worked to create schools and helped teachers become properly trained and credentialed,” said Sr. Betsy. “Many people learned to read and write because of Sr. Dorothy Stang. She also had a vast knowledge of popular health care remedies, particularly useful in areas where doctors and hospitals are scarce, and medication costs are often exorbitant.”

In the last year of her life, Sr. Dorothy was granted naturalized citizenship in Brazil. She received a humanitarian award from a Brazilian lawyers’ association and officials in the state of Para named her “Woman of the Year.” Both honors were given for her work to secure land rights for peasants but while she was given the award from the officials in Para, a plan was underway for a paved highway through the area, raising land values higher and escalating the violence.

At the federal level, President da Silva is caught between a promise to find homes for 400,000 landless families, an expressed desire to protect the rainforest and the pressure to open tracts of forest to support economic growth. External pressure comes from the International Monetary Fund, which loaned Brazil billions of dollars after its 2002 recession. It is a dangerous and complicated life for many in Brazil, but for none more than the people in Para. The Pastoral Land Commission reported recently that the state of Para has been the site of 40% of the 1,237 land-conflict killings in Brazil over the past 30 years. The many concerns surrounding the climate of corruption in Para have increased efforts to move the investigation into Sr. Dorothy’s murder from the state to the federal government. It is widely believed that a fair trial cannot be achieved in Para.

Mary Alice McCabe, SND, who defends the rights of families relying on the fishing trade in Ceara, Brazil, says of Sr. Dorothy: “She was with the excluded migrant farmers in their constant, futile search for a piece of land to call their own. She persistently pressured the government to do its job in defending the rights of the people. She never gave up. She never lost hope.”

Several thousand people attended Sr. Dorothy's funeral. In the month following her murder, four men were arrested and charged with the murder. President da Silva sent 2,000 troops to the area to quell violence, while the United States sent FBI agents to Anapu to investigate the killing. Memorial services were conducted around the world and the Brazilian Ambassador to the United States spoke at a Memorial Mass for Sr. Dorothy in Baltimore. On March 9, 2005, U.S. Congress Resolution #89 was introduced, honoring the life of Sr. Dorothy Stang. On December 10, 2008, Sr. Dorothy Stang was awarded the 2008 United Nations Award in the Field of Human Rights.

She is buried in a grove in Anapu, her grave marked with a simple wooden cross bearing her name and dates of birth and death.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)