At about 1:15 AM on March 27, 1996, some twenty armed men arrived at the monastery of Tibhirine and took seven monks into custody. Two others, Fr. Jean-Pierre and Fr. Amédée, who died in 2008, escaped the kidnappers' notice, hidden in separate rooms. After the kidnappers left, the remaining monks tried to contact the police, but the telephone lines had been cut. Because of the curfew in force, they could only wait until morning before driving to the police station in Médéa.

On April 18, the Armed Islamic Group (GIA - Groupe Islamique Armé) issued communique #43, demanding the release of GIA leader, Abdelhak Layada, as the price for the monks' lives. On April 30, a tape with the voices of the kidnapped monks, recorded ten days earlier, was delivered to the French Embassy. On May 23, the Armed Islamic Group's communique #44 reported that the Armed Islamic Group had killed the monks on May 21. The Algerian government announced that the monks' heads had been discovered on May 31; their bodies were never found. A funeral Mass was celebrated in the Catholic Cathedral of Notre Dame d'Afrique (Our Lady of Africa), Algiers, on June 2, 1996, and their remains were buried in the cemetery of the monastery at Tibhirine on June 4. The surviving two monks of Tibhirine left Algeria, to live in the Trappist annex near Midelt in Morocco, where the late Father Bruno had been superior.

The circumstances of the Tibhirine monks' kidnapping and deaths remain controversial. In 2008, the Italian newspaper La Stampa reported that an anonymous high-ranking Western government official, then based in Algeria and in Finland, had told them that the kidnapping had been orchestrated by a GIA group which the DRS (Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité, the Algerian state intelligence service) had infiltrated , and that the monks had then been killed accidentally by an Algerian military helicopter attacking the camp where they were being held captive. In 2009, the retired French general, François Buchwalter, who was military attaché in Algeria at the time, testified to a judge that the monks had accidentally been killed by a helicopter from the Algerian government during an attack on a guerrilla position, then beheaded after their death to make it appear as though the GIA had killed them. Ex-GIA leader Abdelhak Layada, who was in prison when the monks were killed, but was later freed under a national amnesty, responded by claiming that the Armed Islamic Group had indeed beheaded them after negotiations with the French secret services broke down.

Brother Christian, prior of the Tibhirine monastery, left behind a letter which he had written on New Year's Eve, 1993, to be opened by his community and family in the event of his death. He and the other monks were well aware of the growing tensions in Algeria, and that he, and they, might well become "a victim of terrorism which now seems ready to engulf all the foreigners living in Algeria". In the letter he assures those left behind that, while he doesn't desire such a death, indeed doesn't feel worthy of such an offering, he could never rejoice:

|

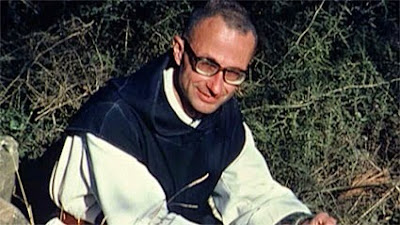

| Brother Christian de Chrege |

"if the people I love were to be accused indiscriminately of my murder. To owe it to an Algerian, whoever he may be, would be too high a price to pay for what will, perhaps, be called, the 'grace of martyrdom', especially if he says he is acting in fidelity to what he believes to be Islam. I am aware of the scorn which can be heaped on Algerians indiscriminately. I am also aware of the caricatures of Islam which a certain Islamism encourages. It is too easy to salve one's conscience by identifying this religious way with the fundamentalist ideologies of its extremists. For me, Algeria and Islam are something different: they are a body and a soul. I have proclaimed this often enough, I believe, in the sure knowledge of what I received from it, finding there so often that true strand of the Gospel, learnt at my mother's knees, my very first Church, in Algeria itself, and already inspired with respect for Muslim believers..."

Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay... come what may. This film is loosely based on the life of the Cistercian monks of Tibhirine in Algeria, from 1993 until their kidnapping in 1996.

ReplyDeleteYouTube Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhQzn2gVGjQ